The EU’s humanitarian aid and civil protection policy in Central Asia: Past crises and emergencies to come

Download “The EU’s humanitarian aid and civil protection policy in Central Asia: Past crises and emergencies to come”

EUCAM-Policy-Brief-29.pdf – Downloaded 420 times – 586.40 KBThe 2007 EU Strategy for Central Asia stresses security and stability through regional cooperation and integration, poverty reduction and good governance. But the strategy hardly mentions humanitarian aid, a security-related activity that not only plays a crucial role in strengthening European soft power in crisis-affected areas, but also predates many of the European Union’s programmes in the Central Asian region. Between 2007 and 2012, the region’s governments requested foreign aid for a dozen humanitarian emergencies. The majority were floods, earthquakes and so-called compound crises caused by exceptionally cold winters, a breakdown in energy supply and the reduction of winter crop yields and livestock. The same period also saw a political emergency with serious communal violence, displacement and habitat destruction. In one way or another, these crises affected around 4.5 million people out of a total population of some 58 million. These emergencies clearly reflect the hazard risks continually faced by the Central Asian region due to its physical and human geography as well as its sociopolitical legacies and dynamics.

Throughout the period, Central Asia reportedly received nearly $347 million of international humanitarian assistance from a variety of OECD (including the EU and its member states) and non-OECD donors. Of this amount, 49 per cent went to Tajikistan, 47 per cent to Kyrgyzstan, 2.5 per cent to Uzbekistan and the remaining 1.5 per cent to Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan.(1) But where does the EU figure in Central Asia’s humanitarian aid landscape? This paper sheds light on the origins, dynamics and evolution of the EU’s relatively unknown humanitarian aid activities in Central Asia. The brief examines the position and modus operandi of the EU as a humanitarian donor in Central Asia, and compares its track record to other interventions in former Soviet regions. Finally, it explores potential future challenges and realities that might shape and (re-)direct the EU’s humanitarian activities in the region.

The EU and Central Asia’s humanitarian space

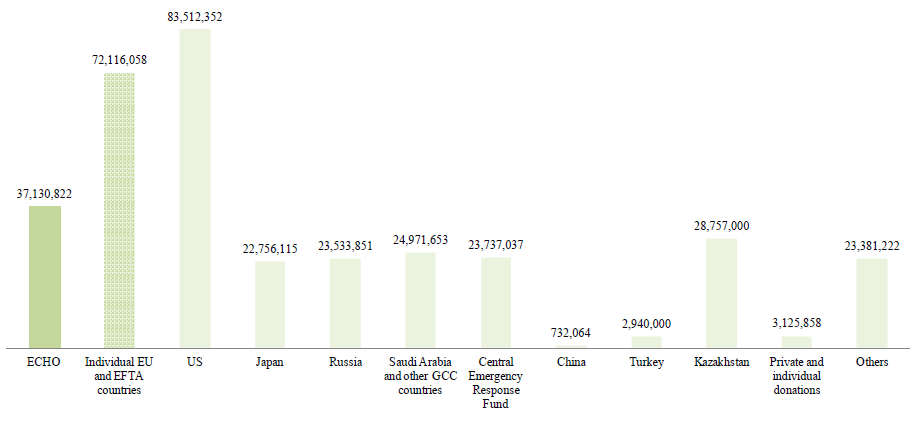

The EU, through the European Commission Humanitarian Office (ECHO) and, latterly, the Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection department, is the largest individual aid donor to the region after the United States.(2) If bilateral aid provided or committed by individual EU countries during the reference period is added, then the EU’s overall share in humanitarian aid to Central Asia becomes considerably larger. So, the EU space is in fact the largest humanitarian donor to the region, even if its share and position differ in each emergency situation.

The EU’s position among humanitarian donors to Central Asia between 2007 and 2012 (with respective aid value in U.S. dollars)*

*Graphic created by the author on the bases of figures from OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service database, http://fts.unocha.org. As such, it reflects only official aid that has been reported by donor structures and governments to the OCHA-FTS, and not the actual extent of aid sent and committed to the region.

The EU’s humanitarian presence in Central Asia goes back to the years following ECHO’s operationalisation. It focused from the first, as it still does, on Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. The EU’s humanitarian aid predates its development and technical assistance programmes. ECHO’s activities primarily responded to the rural livelihood crisis that followed the collapse of the centralised Soviet economic system, with its guaranteed markets, subsidies and social services. The crisis was particularly severe in high-altitude areas in Kyrgyzstan and the Tajik region of Gorno-Badakhshan. ECHO also offered assistance to deal with Central Asia’s largest complex political emergency, the 1992-97 Tajik Civil War. In 1994 and 1995, part of the EU’s humanitarian assistance consisted of a €250 million Directorate-General for External Relations (now European External Action Service, EEAS) cooperation framework. This framework also covered the South Caucasus, which has a similar physical terrain and Soviet legacy.(3) In the parts of Tajikistan that saw the most intense fighting, destruction and displacement during the civil war, the EU prioritised house reconstruction, the rehabilitation of water supply and irrigation, and the return and reintegration of refugees and internally displaced people (IDPs). These activities also helped generate income in the region, since they supported local roof tile factories which offered local employment. In areas where acute food insecurity was caused by road blockades, a harsh climate and short farming seasons, EU activities focused on food aid and agriculture. There were no multi-country initiatives and projects in the 1990s. During this period, a number of pilot activities were also set up in a sector that is today ECHO’s operational priority in Central Asia: disaster preparedness. Examples in Tajikistan included the installation of earthquake sensors, public awareness campaigns and the identification of safe spots in villages around Lake Sarez, and the construction of riverbank infrastructure against floods in Garm.

How did this compare to ECHO interventions in other former Soviet regions and in the Western Balkans? The amount of European humanitarian spending per capita as a regional average, similar to spending on the Transnistrian conflict, was limited as compared to per capita spending on the Western Balkans, the South Caucasus and, especially, Chechnya. Central Asia was clearly not a major priority. This is because only a limited number of large complex political emergencies and other ‘aid-triggering’ events took place in the region. Also, the Central Asian crises had a much smaller presence on the mental map both of the public at large and of decision makers in Western Europe. With wars raging in the Balkans and the Caucasus, closer regions had obvious needs, whereas Central Asia was further away, less known and relatively more peaceful. Another factor was and is the limited accessibility of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, due to local authorities’ reluctance to allow large amounts of foreign aid activities, which are perceived as having underlying ideological agendas.

| Region | Total spending (€, million) | Start of operations within the period of reference | Population (2000, million) | Quantity of aid/ inhabitant ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central Asia | 296.8* | 1993 | 56.65 | 5.2 |

| Western

Balkans** |

2,300 | 1991 | 27.1 | 34.8 |

| South

Caucasus° |

499 | 1992 | 15.53 | 32.1 |

| Chechnya | 147† | 1999 | 0.73°° | 188.4 |

| Moldova/ Transnistrian

conflict |

5.5‡ | 1992 | 3.5¹ | 1.57 |

* Nearly 70 per cent of this total went to Tajikistan.

** Former Yugoslavia (armed conflicts in Bosnia, East Slavonia, Kosovo and

Macedonia) and Albania.

° Armenia (natural disasters, economic unravelling and refugees from Azerbaijan), Georgia (the South Ossetia and Abkhazia conflicts) and Azerbaijan (IDPs from Nagorno-Karabakh).

† EU aid figure for the Second Chechen War (August 1999-May 2000) and its

aftermath.

‡ Mainly for healthcare and for IDPs from the Transnistrian conflict. Food security- oriented activities in Moldova, part of it under ECHO or as a spin-off of humanitarian activities, amounted to €15.9 million in the period.

°° Plus 47,000 Chechens internally displaced in Ingushetia.

¹ Of whom 0.55 million were in Transnistria.

The interface of sustainability

ECHO’s main operational framework in the region is a multi- country Disaster Preparedness (DIP) programme known as DIPECHO. DIPECHO is a global €255 million programme that was launched in 1998. Its official goal is to increase communities’ capacity to cope with disasters and to decrease disaster risks and impacts. In 2003, Central Asia, together with the South Caucasus, became the sixth region to participate in the programme, which is currently in its seventh phase. Similarly to the operations in the 1990s, DIPECHO runs few projects or operations on its own; mainly, it looks to partner organisations, such as NGOs, the UN and UN-affiliated organisations, for implementation. These groups thus function as ‘aid subcontractors’. ECHO also has a permanent framework agreement with the International Federation of the Red Cross (IFRC) to work with Central Asia’s national Red Crescent Societies. Over the last 10 years, around €35.5 million has been distributed to some 90 disaster preparedness activities in Central Asia, all of which were implemented by various non- governmental and intergovernmental organisations.

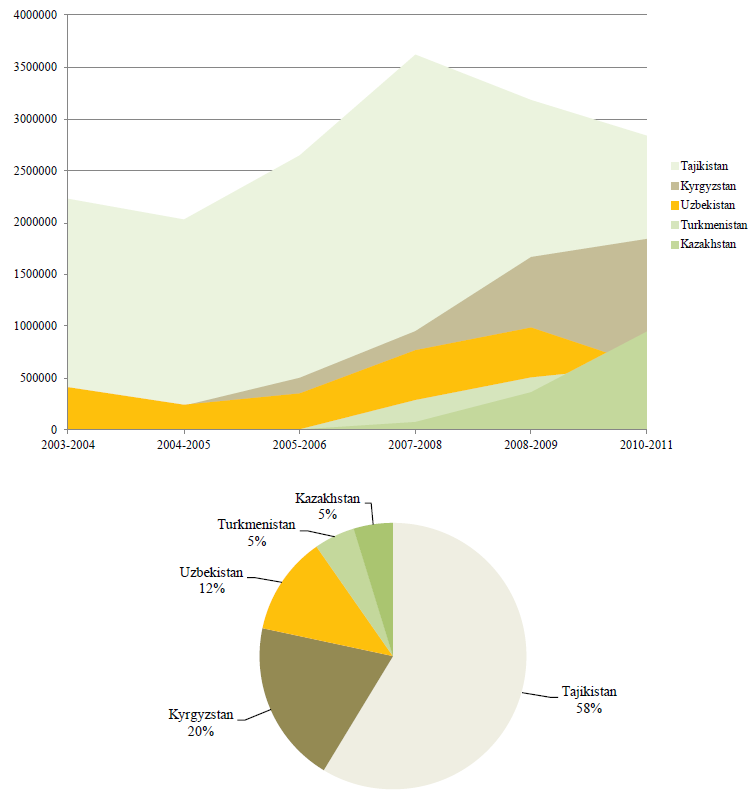

Tajikistan continues to be ECHO’s main recipient in Central Asia, although, due to the stabilisation of the country, its overall portion is shrinking as compared to the 1990s and early 2000s. Kazakhstan’s growing share after 2008 and 2009 has much less to do with disasters or with inability to meet relief needs than with the active role that the country’s government wants to play in regional disaster preparedness. It hopes to achieve this through the EU-supported Central Asian Centre for Disaster Response and Risk Reduction (CACDRRR) which is set to open in Almaty.(5) Currently, DIPECHO works with ten partner organisations active in Central Asia. Several of the implementers are long-standing ECHO partners that have been working in the region since the 1990s. They work with local partner NGOs and community-based organisations, often those who were involved in their previous activities.

ECHO also still funds aid operations outside of its DIP framework, such as the delivery of emergency water and sanitation after the mudslides in Garm, Tajikistan, and the establishment of temporary shelters and house rehabilitation after the 2011 Batken earthquake in Kyrgyzstan. The largest extra-DIP contribution, however, took place after the severest political emergency in Central Asia since the Tajik Civil War: the June 2010 communal violence in southern Kyrgyzstan. This crisis has so far attracted a reported total of $128.9 million of aid. The EU gave $8.46 million in food and shelter as well as psychosocial assistance, especially through ACTED, MSF- Switzerland and UNHCR, making it the third largest individual donor after the U.S. and the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund. ECHO did not fund any relief operations for displaced and homeless people during the fighting between government forces and irregular armed groups in Khorog and Ishkashim, Tajikistan, in 2012. Potential for monitoring was limited due to the closure of the area during the crisis and because the Tajik authorities themselves provided some aid in an attempt to regain goodwill among the population in these sensitive mountainous border districts, far away from the capital.

ECHO’s main Central Asia office has for a long time been located in Dushanbe, both because Tajikistan is ECHO’s main recipient country and because the country is close to Afghanistan. ECHO’s Central Asia office is soon to be moved to Almaty, however.(6) Although Kazakhstan has never been a major recipient of ECHO aid and is itself becoming a donor country, according to ECHO respondents, the move is aimed at consolidating the EU’s emphasis on regional disaster preparedness. The same sources said that Almaty is closer to potential natural and industrial hazard areas. And it provides a more adequate hub for ECHO staff and experts for travelling within and to Central Asia and the South Caucasus, which is also covered by the Almaty office. Lastly, the relocated ECHO office will be able to link up more easily with other regional aid coordination and civil protection institutions, such as the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs and the Central Asian Centre for Disaster Response and Risk Reduction, which have also chosen Almaty as their regional base.

The evolution and overall share per Central Asian country of EU humanitarian aid since the launching of ECHO’s Disaster Preparedness (DIPECHO) framework (in €, 2003-2011)*

*Graphic created by the author on the basis of an ECHO spreadsheet.

*Graphic created by the author on the basis of an ECHO spreadsheet.

Considerations and possible shifts

DIPECHO’s current phase runs until late 2013. Throughout its past and present cycles in the region, the programme has sought to balance grassroots projects with policy development in disaster preparedness, situated on the interface between relief and long- term development.(7) DIPECHO’s stated purpose is to create sustainability, preparing recipients to maintain all mechanisms themselves. But most regional and international aid-delivery experts believe that prospects for meeting this objective in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are dim. In both countries, dependency on foreign aid has become ingrained in the mentalities of the relevant structures and actors. Relief efforts in the acute phase of emergencies remain generally appreciated by the population. But a substantial part of the public feels aid fatigue, if not outright cynicism, about the real and perceived hidden agendas that drive aid, especially when it comes to policy and capacity-building programmes. These initiatives are often regarded as opaque ventures, consisting of consultancies and seminars rather than presenting tangible results. Another question is whether ECHO’s practice of working with sub-contracted Europe-based NGOs and their local NGO sub-contractors is enhancing the self- sustainability of a closed NGO caste rather than encouraging capacity building in the broader communities.

The EU will remain a major humanitarian donor to Central Asia in the years to come. However, its working space and legitimacy will unavoidably be affected by the emergence of donor countries from outside the OECD, including Kazakhstan. Between 2000 and 2012, Kazakhstan officially spent some $63.6 million on humanitarian assistance, of which over a third was spent in different Central Asian contexts and a quarter in Afghanistan.(8) At the grassroots level, remittances from international and intra- regional labour migration are an important source of income (especially in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan) and feed a new economic dynamic (more so than foreign aid does). These remittances have also made communities economically and socially more resilient to disaster-related setbacks than in the 1990s. The test for the EU’s disaster preparedness efforts will eventually come from emergencies and crises whose occurrence and humanitarian consequences are difficult to predict. Alongside natural and technical hazards, new or renewed complex political emergencies within the region should be taken into account. Even if no real ‘chain reaction’ from the Arab uprisings is to be expected in Central Asia, the violent turns that protests and government reactions took in Libya and Syria are a reminder that some Central Asian countries with authoritarian regimes and artificial stability ‒ for instance, Uzbekistan – have the potential for serious unrest, violent political change and internal as well as cross-border displacement. This scenario should be reckoned with in ECHO’s planning for the region.

| Implementing organisation | DIPECHO-funded project activities and direct beneficiaries | Countries and areas or institutions |

|---|---|---|

| Agence d’Aide à la Coopération Technique et au Développement (ACTED) | Increase cross-border cooperation for disaster response, at both government and community levels – 99,000 beneficiaries. | Rural communities in the Kodibardigan and Isfara river basins, south-western Kyrgyzstan and northern Tajikistan. |

| Deutsche Welthungerhilfe | Upgrading of disaster and risk management techniques among communities and institutions (district and municipal governments and local sections of the Red Crescent Society) – 17,500 beneficiaries. | The districts of Garm, Darband and Tajikabad in eastern Tajikistan. |

| Focus Humanitarian Assistance | Improving disaster resilience in mountain communities and with institutions (municipal governments and community organisations) – 54,400 beneficiaries. | The Gorno-Badakhshan region of Tajikistan and the Osh and Alay areas in southern Kyrgyzstan. |

| International Organisation for Migration | Disaster management training and equipment upgrading for the governmental Civil Protection and Rescue Department of the Ministry of Defence, the national Red Crescent Society and selected communities in disaster-prone areas – 5,300 beneficiaries. | Turkmenistan, both Ashgabat and the said institutions’ branches in all five provinces. |

| Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) | Strengthening of disaster response and relief coordination structures in Central Asia and the Southern Caucasus – 66 direct beneficiaries in the 8 countries. | Relevant national institutions. |

| Oxfam-Great Britain | Capacity building of local NGO partners, communities and local authorities in emergency planning, both task-specific and long range – 11,800 beneficiaries. | Kulyab, Vose and eight other districts in southern Tajikistan. |

| Save the Children-Netherlands | Disaster risk reduction, preparedness (evacuation spots, supplies, ID cards) and awareness raising among teachers and children and educational institutions in a total of 50 village schools – 42,070 beneficiaries. | A total of 50 villages in the Vakhsh valley in Tajikistan, the Naukat and Kara-Kulja districts in Kyrgyzstan and Tashkent province in Uzbekistan. |

| UNICEF | Training of children and schools to better prepare for and respond

to disasters – some 71,700 beneficiaries. |

Almaty city and province and Southern Kazakhstan province, Batken and Leilek districts in Kyrgyzstan, the districts of Ayni, Garm and Kulyab in Tajikistan, and 20 locations in the capital and the five provinces of Turkmenistan. |

| United Nations Development Program | Support for local-level measures to minimise the damage from flooding and landslides, public awareness raising on disaster preparedness and risk reduction – 31,620 beneficiaries. | Teqeli (Almaty province) and villages around Semipalatinsk and Ust-Kamenogorsk (East Kazakhstan province), the Ministry of Emergency Situations and the Red Crescent Society of Kazakhstan. |

| Earthquake simulation centre. | Tashkent, Ministry of Emergency Situations of Uzbekistan. | |

| World Health Organisation | Improve the management of a large number of casualties in the event of a disaster – 270 beneficiaries. | The Ministries of Health and of Emergency Situations of Tajikistan. |

*Table compiled by the author on the basis of figures from OCHA’s Financial Tracking Service database, an ECHO project spreadsheet provided to the author, and the different project sheets and portals of the implementing organisations.

The EU’s humanitarian policy in the Central Asian region will also be affected by how the security and humanitarian situation in neighbouring Afghanistan evolves after the direct international presence largely ends in 2014. Insecurity and local hostility to Western donors and aid organisations could restrict aid workers’ access to the southern parts of Afghanistan and to land supply routes via Pakistan. So, Central Asia will most likely become a backup base and an alternative aid supply route ‒ especially through Termez, the Osh-Khorog route and the Tajik-Afghan border ‒ to the northern parts of Afghanistan, much as it was between 1998 and late 2001. Growing instability in northern Afghanistan could also result in refugee movements into Central Asia. However, during the 1992-96 factional war in Afghanistan after the overthrow of the Afghan socialist regime, such north- bound refugee movements were very limited compared with those to Iran and, especially, to Pakistan.

Conclusion

Potential intra-regional political unrest and spillover from Afghanistan, should they materialise, will lead to a reorientation from disaster preparedness to classical emergency aid. Overall humanitarian funding to Central Asia has been decreasing in recent years. But the anticipation of new natural and technical hazards and complex political emergencies, both in the region and in adjacent areas, makes humanitarian aid a highly volatile sphere. ECHO and other aid actors need to maintain a presence and operational framework in the region. To achieve this, ECHO could more closely integrate part of its operational structures and activities in Central Asia with those in the Afghan provinces adjacent to the region. This could take place either through a liaison or field office, in cooperation with OCHA or through long- standing NGO partners who work on both sides of the border. In anticipation of future emergencies in the region, the focus on sub- contracting EU-based NGOs could be revised in favour of a larger and more pro-active role for the EU Civil Protection Mechanism, with an emphasis on shorter interventions during early and acute crisis phases.9 Lastly, in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the ECHO focus should be on capacity building. Where possible, aid should be substantially reduced, to decrease the overdependence on foreign aid, which has become something both countries take for granted, leaving little means or incentive to strengthen their own structures.

- Figures calculated by the author on the basis of data in the Financial Tracking Service (FTS) database of the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), http://fts.unocha.org/.

- The European Commission Humanitarian Office (ECHO) was created in 1992, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1996R1257:20090420:EN:PDF, and became fully operational in 1993. In October 2010, it was merged with the European Civil Protection Mechanism (ECPM, established in 2001) to form the Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection department, which is still commonly referred to as ECHO. ECHO’s operations in Central Asia are dealt with by its Regional Support Office for Central Asia, the Caucasus, the Mediterranean and Middle East in Amman (Jordan).

- ECHO’s main implementing partners in Central Asia during the 1990s and early 2000s were UNHCR, UNOPS, WFP, the IFRC, Caritas-Switzerland, ACTED, Médecins Sans Frontières, Deutsche Welthungerhilfe (which is particularly active in Garm), Pharmaciens Sans Frontières and Focus Humanitarian Assistance (which has a strong position in Gorno-Badakhshan).

- Table compiled by the author on the bases of data from ECHO regional fact sheets and activity reports on the Balkans and Chechnya, the European Neighborhood and Partnership Instrument’s Moldova country strategy paper for 2007-2013, ECHO annual reviews and spreadsheets provided during meetings with ECHO staff.

- The CACDRR project reflects, among other things, the intention of Kazakhstan’s government to extend its leading position in the Central Asian region to the field of disaster management. The three states and their Ministries of Emergency Situations that are so far participating in the centre are Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.

- The EC Delegation in Kazakhstan is in Astana, the country’s political and administrative capital. Besides the office in Dushanbe (and now Almaty), which has one international and five regional staff but is set to expand, DIPECHO Central Asia and Caucasus has a small liaison office with one staff member in Tbilisi, Georgia, which was opened during the South Ossetia War in 2008.

- Some of ECHO’s livelihood and food security activities in Central Asia are to be integrated in the rural development programmes of the EC’s Development and Cooperation directorate.

- Figures calculated by the author on the basis of data in the Financial Tracking Service (FTS) database of the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), http://fts.unocha.org/.