European National Policies Series – The Baltic sates and Central Asia

Download “European National Policies Series - The Baltic sates and Central Asia”

After a long period of minimal contact given their different political and economic choices after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the three Baltic countries and the five Central Asian states now have well- established, positive political relations.(1)

In the past, trade relations between Central Asia and the Baltic countries focused mainly on logistics and transit services, given their common transportation infrastructure inherited from the Soviet period, most importantly, the rail network. However, Kazakhstan’s rapidly growing economy coupled with the effects of the financial crisis on the Baltic countries have pushed the latter to search for new business opportunities and to engage more actively with the Central Asian region. Most major bilateral projects are still linked to transit, but opportunities in technology transfer, agriculture, tourism and education are also being explored. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are all interested in developments regarding alternative energy supply routes via the Caspian Sea, but they are not directly involved with Central Asia’s energy market.

Security is a priority, mostly because of the Northern Distribution Network (NDN) used to transfer supplies from Baltic ports through Central Asia and the Caucasus to Afghanistan. This supply route is important for the Baltic countries from the perspective of transit, prosperity and security, especially in view of the NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014. The NDN could also potentially offer future trade and transit opportunities. However, these do not feature high on the current agenda and will depend on the future security and stability of Afghanistan. Central Asia is thus seen as a challenging yet promising region for the Baltic states.

Political relations and values

All three Baltic countries have embassies in Central Asia. Latvia was the first country to open an embassy in Uzbekistan in 1992; the embassy in Tashkent also covers Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan and Afghanistan. Twelve years later, in 2004, Latvia opened an embassy in Kazakhstan with the intention of increasing bilateral trade and investment opportunities in the country. For several years, a Latvian Investment and Development Agency delegate was also present in Almaty, Kazakhstan’s former political capital and which is still the country’s commercial capital. However, the delegate had to be called back to Riga because of the financial crisis. Lithuania opened an embassy in Kazakhstan in 2004, covering also Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. The Lithuanian ambassador to Azerbaijan also provides representation to Turkmenistan. Estonia was the last Baltic state to establish a presence in the region, opening in 2011 an embassy in Kazakhstan, which is responsible for the whole Central Asian region.

All three Baltic countries have established good working relations with Central Asian authorities, resulting in regular high-level visits. In 2011, the Lithuanian president visited Astana. In 2012, alongside various regular parliamentary exchanges and ministerial consultations, Turkmenistan’s president paid an official visit to Latvia and Kazakhstan’s president conducted a two-day state visit to Estonia. All three countries have established contacts at the parliamentary level, which also have led to several bilateral visits. For example, Kazakh and Kyrgyz parliamentarians have visited the Latvian and Lithuanian parliaments to learn more about the experience and mechanisms of Baltic countries’ parliamentary processes.

The Baltic states fully support the European Union (EU) and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) in promoting common values such as democracy, human rights and the rule of law in Central Asia. However, their primary bilateral interests regard increased trade and economic ties. Thus they are not particularly vocal on human rights or rule of law issues during bilateral visits, for fear of endangering their trade relationships. In addition, Baltic countries have neither the financial nor the human resources to engage in bilateral development or human rights projects in Central Asia. Instead, they make an indirect contribution through national experts who engage in OSCE or EU projects, or through development cooperation in specific areas such as justice reform. Nonetheless, the Baltic countries’ first-hand experience of transition from the Soviet political and legal system, as well as their subsequent reforms in terms of good governance and the rule of law, represent a wealth of knowledge from which Central Asia could benefit. The Baltic countries could use this reform experience to help the Central Asian countries, as they are currently doing in Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova.

Trade and energy

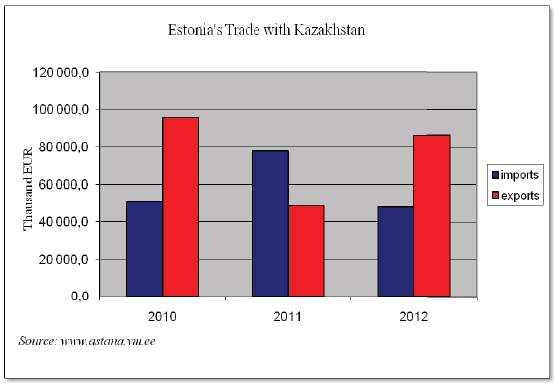

The dire consequences of the financial crisis in the Baltic countries have pushed the governments of the region to reconsider certain aspects of their foreign policy. Economic growth, new market opportunities and attracting foreign investment are now very high priorities. The opening of the Estonian embassy in Astana in 2011 can be seen as a direct result of business lobbying to strengthen bilateral ties so as to explore trade and commercial opportunities in Kazakhstan.

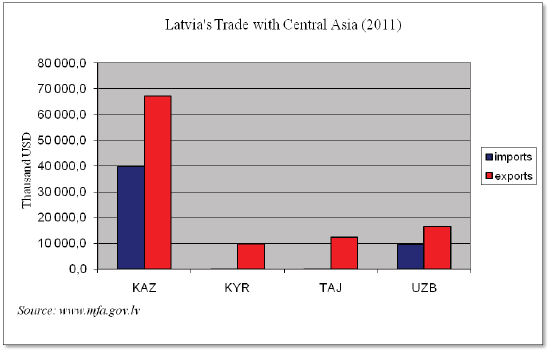

Kazakhstan is the main trading partner in Central Asia for all three Baltic countries. For a long time, the main commerce area was transit services and logistics, based on the inherited Soviet railway system that connects Baltic ports with Central Asia. Even now, despite attempts to explore new trade opportunities, many major bilateral commercial projects concern logistics and transit services. For example, in 2012 Lithuania launched the shuttle container train Saule (Sun). This train runs from the Klaipeda port in Lithuania to the Chinese city of Chongqing through Almaty in Kazakhstan, shortening the transportation time of goods to Almaty to eight days and establishing Klaipeda as a logistics bridge between east and west.

Recent bilateral visits have indicated willingness on both sides to enter into more broad-based discussions. During Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s visit to Estonia, aside from new transit opportunities, technology transfer, e-government and shipbuilding were also discussed. This resulted in a deal between Kazakhstan and the Estonian company BLRT to build ferryboats that will run on liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the Caspian Sea, linking Kazakh and Azerbaijani ports. Estonian entrepreneurs are also looking into the special economic zones offered by Kazakhstan, as well as examining potential cooperation on agricultural trade, cattle breeding, environmental issues, cyber crime, education and research.

Latvia, along with transit services, is focused on developing cooperation in agriculture, metalwork and pharmaceuticals. In addition, several Latvian banks have a presence in Central Asia. The Kazakhs have invested in a grain terminal in Ventspils, a seaside port city in Latvia. Some of Kazakhstan’s elite are also keen on purchasing properties in Latvia to take advantage of the opportunity to gain long-term residence permits in the EU. Nevertheless, commercial expansion is limited due to the distance and cost of goods transit, as well as the bureaucracy involved. Another obstacle is the fact that Latvian mid-range enterprises cannot always afford to provide the large volumes of products needed for Kazakhstan’s markets. One promising solution to this problem would be the establishment of a joint-venture company, similar to the existing ‘Riga Courtyard’ in Moscow, which would offer a wide range of Latvian products in one shop.

Lithuania has successfully entered Kazakhstan’s food market, offering dairy and fish products, as well as investing in the production of soft drinks. The sale of second-hand cars, transported from Lithuania to Astana by rail, also makes up a significant part of bilateral trade. All three Baltic states are interested in building cooperation with Kazakhstan on tourism and education. The lack of direct flights between Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and Kazakhstan is viewed as the main obstacle successfully to develop tourism ties.

Energy matters may become an important focus in the future. The Baltic countries are extremely dependent on Russian energy supplies and are concerned about the construction of the Nord Stream gas pipeline, which bypasses Baltic ports. Although they are not directly involved in the energy market, they are closely following developments on alternative energy supply routes from Central Asia via the Caspian to Europe. However, the construction of alternative gas routes through the Caspian, Azerbaijan and Turkey might not benefit the Baltic region, as most of the gas will most likely be bought by other EU countries before reaching the Baltic states.

Security

Lithuania is the most active on security cooperation in the region. It is the only country with a defence attaché in the region, which has led to several agreements and joint military exercises. Recently, Lithuania signed a military cooperation plan with Kazakhstan for 2013, which foresees information exchange on security matters and involvement in multinational operations and military reform. In addition, Lithuania regularly participates in the Steppe Eagle joint military exercises with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and other NATO countries. Since 1997, this initiative has been working to improve the readiness of peacekeeping units to take part in NATO-led operations.

Both Lithuania and Latvia have engaged with Central Asia on ‘soft’ security issues such as border management, training and the rule of law, mostly within the framework of the OSCE, the UN or the EU Border management programme in Central Asia (BOMCA). Latvia has experience training Central Asian border guards and customs officers under the auspices of BOMCA. Lithuanians have participated in similar training initiatives with Afghan and Tajik border guards within the framework of the OSCE. So far, Estonia has not engaged with Central Asia in a structural way on security matters.

All three Baltic countries are NATO members and have contributed troops to Afghanistan. They play an important role in the Northern Distribution Network, especially in light of the upcoming U.S. and NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014. The NDN is very important to all three Baltic countries, both in terms of their role within NATO and their security concerns as well as for transit opportunities from their ports in Tallinn, Riga and Klaipeda. Future trade and transit opportunities will very much depend on Afghanistan’s security and stability. If the security situation is stable, the established transport corridor could serve as a tool to integrate Afghanistan and Central Asia into the world economy. NATO membership is seen by the Baltic nations as the foundation for their own national security, so NATO policy and concerns regarding Central Asia are fully supported by the Baltic states. In 2012, Latvia became the NATO Contact Point embassy in Kazakhstan, working to support the alliance’s partnership and public diplomacy activities.

Development assistance

Central Asia is not a priority region for Baltic states in terms of bilateral development aid. Due to financial constraints and a development focus on Afghanistan, none of the Baltic countries provides financial support for bilateral development assistance projects in Central Asia beyond a number of ad hoc initiatives. For example, Estonia has recently granted a fellowship to Tajik diplomats to study at the Estonian School of Diplomacy.

The Baltic states do not have the financial or human resources to carry out bilateral development projects. But they could offer know-how on specific cost-free issues linked to awareness raising, social issues and well-being. For example, Estonia has launched a regional campaign with local authorities in Ukraine on road safety practices among children. The programme led to a significant decrease in traffic accidents involving children. This kind of projects does not need financial input, so much as a willingness to share best practices and expertise. Currently, the Estonian embassy in Astana is considering undertaking a similar project in Kazakhstan.

Baltic NGOs are not very active in Central Asia and occasionally participate as invited experts in EU civil society projects. However, this area could offer many opportunities if developed further. Baltic NGOs have first-hand experience in state reform on rule of law or good governance, as well as in promoting civic participation and engagement.

All three Baltic countries see education as a promising area for cooperation with Central Asia. Latvia has a long-established collaboration with Kazakhstan’s technical, medical and air navigation institutes, partially due to its capacity to teach subjects in Russian. Lithuania has similar networks, mostly involving medical students. The Tallinn and Tartu Universities in Estonia have recently been included in the Bolashak programme, a national scholarship programme for Kazakh students to study abroad. All three Baltic countries are eager to strengthen cooperation between their education facilities as part of their on- going search for new ways to attract students to their universities.

Conclusion

Given the financial pressures at home, the Baltic countries have begun to take a closer look at Central Asia and at the business opportunities in the region, especially in Kazakhstan. Hence, bilateral relations are strongly focused on exploring and developing trade cooperation in areas such as agriculture, pharmaceuticals and shipbuilding. Education and tourism are also considered to be potentially lucrative areas of cooperation, with good foundations due to the common lingua franca and inherited infrastructure networks from the Soviet era.

Energy and security are important for Baltic countries, but are difficult areas to gain leverage and do not depend on bilateral relations with Central Asia. Although Baltic countries are very interested in alternative energy supplies, they do not play a leading role in the Central Asian energy market. It is unlikely that Baltic countries will benefit from gas pipelines bypassing Russia from Central Asia via the Caspian to Europe. In terms of security, the Baltic states are very interested in the NDN because of the transit opportunities it provides. Nevertheless, the NDN depends on NATO countries in Afghanistan making transit agreements with Central Asian governments, and the Baltic countries would have difficulty influencing progress in this area.

The Baltic states have valuable experience in moving from a rigid Soviet system of governance, rule of law and state-regulated economy to democracy and open market economies. Currently, this knowledge is overlooked due to the focus on trade relations. Baltic states should make use of this well-grounded, realistic and less costly expertise to engage more fully in promoting democratic reforms and economic liberalisation in Central Asia. This, in turn, would also benefit the Baltic countries.

- To explore the current state of bilateral relations between Central Asian and Baltic countries, interviews were conducted with the Estonian and Latvian ambassadors to Kazakhstan, Jaan Hein and Juris Maklakovs, and with the Lithuanian ambassador to Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, Rokas Bernotas.

Download “European National Policies Series - The Baltic sates and Central Asia”

EUCAM-National-Policies-Brief-11.pdf – Downloaded 373 times – 561.15 KB