Uzbekistan opening up

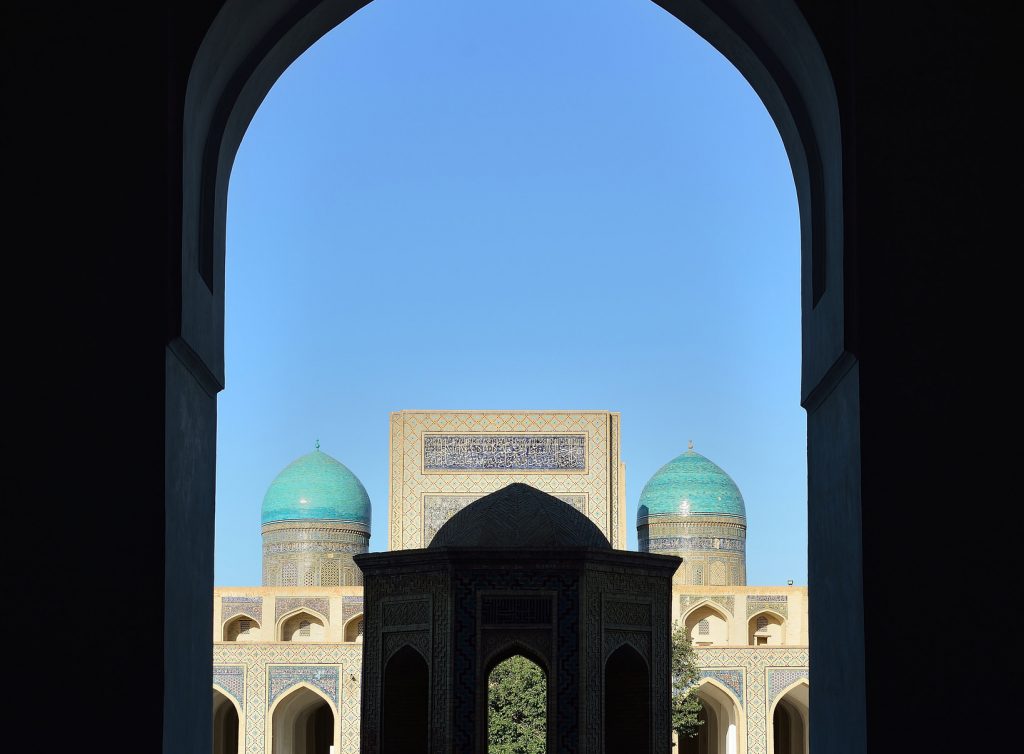

Photo by Henrik-Berger-Jorgenson via Flickr under Creative Commons license

Download “ "Uzbekistan opening up"”

EUCAM-Watch-19.pdf – Downloaded 819 times – 484.67 KBOptimism and doubt…

Uzbekistan has begun to take steps towards openness and economic and political reform. Since the death of President Islam Karimov in September 2016 and the parliamentary appointment of Shavkat Mirziyoyev as the new President of the Republic, Uzbekistan has improved relations with its neighbours and started a process of internal reform. Despite these positive signs, it is still too early to estimate the extent of Uzbekistan’s political transformation over the coming years.

The Uzbek government is rejuvenating the civil service with the appointment of new young faces, releasing political prisoners and opening up space for civil society and media, while indicating to international partners that it is open to cooperation and foreign investments. All this has been set in motion without external pushes for democratisation or economic incentives from external partners. Given that Uzbekistan has been a ‘closed country’ for so long, there are only a handful of international donors active in the country. While there is now a renewed interest among the donor community to develop partnerships and implement democratisation projects in Uzbekistan, it is still unclear where the focus should be, as the Uzbek government seems to be open to almost anything. Uzbekistan is also establishing better and more practical relations with neighbouring republics, particularly on border issues and water management. Whereas so far Uzbekistan has focused mainly on improving bilateral ties and does not yet seem inclined to join regional and international fora, Tashkent’s opening could potentially translate into new opportunities for regional cooperation.

External observers welcome these changes but are not yet convinced that democratic reforms will take root. At the moment, reforms have only scratched the surface, leaving the main institutions – parliament, government and the judiciary – untouched. It is also unclear what the views of the country’s elites are. If current reforms do not bring quick benefits for the elites, there is a risk that further reforms will be stalled (not much has been done so far to counter corruption, for instance). In addition, should the President feel threatened by these increased freedoms, reforms could be reversed. Regional openness could also backfire should neighbours feel that Uzbekistan’s ‘trade openness’ could hurt their own markets or that a more active Uzbekistan could lead to a (renewed) rivalry between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan for regional leadership.

The European Union (EU) is one of the few international donors active in Uzbekistan. After the full lifting of sanctions in 2010, the EU opened a Delegation in Tashkent in 2011. The EU had found it difficult to work with the previous government and allocate funding to meaningful projects. Now, the EU might be overwhelmed by the possibilities and the demand for cooperation. Brussels has indicated its disposition to discuss an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) with Uzbekistan that would replace the current standard partnership and cooperation agreement. However, before tying itself to an EPCA, the EU and Uzbekistan should draft and implement a modest 1-2-year action or cooperation plan, making use of unspent funding earmarked for Uzbekistan under the current Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI). Such a plan could consist of a package of targeted projects aimed at democratic reform, coordinated by the EU, implemented by Uzbekistan, and supervised by both. This could be a good test case for EU-Uzbekistan cooperation. First, on the one hand, it would show the EU that Uzbekistan is serious about reform and, on the other hand, convince Uzbekistan that the EU is an important cooperation partner. Second, it could help set priorities for EU development cooperation funding under the new funding cycle as of 2021. And third, a positive track-record of cooperation could further pave the way for successful EPCA negotiations. Should the EU want to start EPCA talks as soon as possible – to include this in the new 2019 EU-Central Asia Strategy – such an action plan should be implemented whilst negotiations are ongoing, but not after.

In June, policy-makers, researchers, and civil society representatives debated about reform in Uzbekistan at a roundtable organised in Brussels by the EUCAM programme of the Centre for European Security Studies (CESS) based in Groningen, the European Neighbourhood Council (ENC) based in Brussels, and the Open Society Europe Policy Institute (OSEPI), also based in Brussels. In this EUCAM Watch, you will find short interviews with the speakers, including EUSR Peter Burian and OSF programme officer Alisher Ilkhamov, regarding their views on Uzbekistan’s democratic reform and regional cooperation in Central Asia.

Editorial by Jos Boonstra – EUCAM Coordinator, Centre for European Security Studies, Groningen, and Andreas Marazis – Head of Research for Eastern Europe and Central Asia, European Neighbourhood Council, Brussels.

Download “ "Uzbekistan opening up"”

EUCAM-Watch-19.pdf – Downloaded 819 times – 484.67 KB