European National Policies Series – Eastern Europe and Central Asia

Download “European National Policies Series - Eastern Europe and Central Asia”

EUCAM-National-Policies-Series-3.pdf – Downloaded 330 times – 1.36 MBRelations between Central Asia and the post-Soviet countries of Eastern Europe have largely been developed in the shadow of Russia. Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine have established ties through integration projects in the post-Soviet space that are led by Russia, such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and other initiatives. But against this, bilateral and multilateral relations between CIS countries have often been aimed at counterbalancing Russia’s dominance. GUUAM, for example, was an alliance between Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Moldova formed in 1999; after the departure of Uzbekistan in 2005, it became known as GUAM. The organisation was conceived as an alternative cooperation project, and Moscow perceived it to be anti-Russian.

Ukraine has developed bilateral relations with Central Asian states in the hope of diminishing its dependence on Russian gas. Belarus has promoted relations in order to diversify trade flows and boost its exports, so as to lessen its economic and political reliance on Russia. Moldova however, has little interest and possesses few ties with Central Asia.

The post-Soviet countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia share membership in an array of regional organisations and some of the countries have deep trade and economic links. But in general, Central Asia is marginal to the foreign interests and policies of Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine. For many years, despite their different priorities and stages of integration into European and Eurasian projects, the foreign policies of all three countries have focused on the two poles of Brussels and Moscow and the search for balance between them. Where foreign policy is concerned, the EU and Russia absorb most of the attention of politicians, diplomats, researchers, journalists and the wider public in Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine.

Political relations

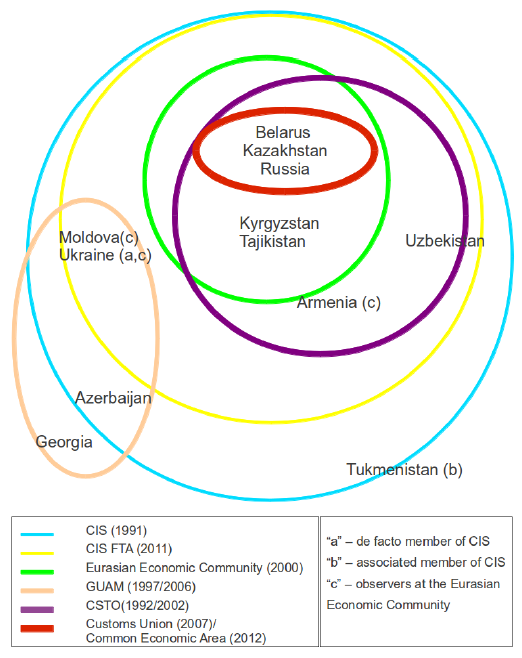

The countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia are linked by their membership in post-Soviet regional organisations. One platform for political socialisation between Eastern European and Central Asia elites is provided by the regular summits and meetings of foreign affairs ministers and heads of government agencies held under the auspices of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Some of the states are tied even more closely by their membership in economic and security organisations. In terms of economic and security orientation, post-Soviet countries can be broken down into two groups. Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are reliant on Russia in their foreign economic and security strategies. Ukraine, Moldova, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan prefer to keep their distance and resist Eurasian integration.

Belarus and Kazakhstan share membership in all of the Moscow-led organisations in the post-Soviet space. Belarus is a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) along with Russia, Armenia and all of the Central Asian republics apart from Turkmenistan. Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are members of the Eurasian Economic Community (EAEC), which was formed in 2000. Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan endorsed the idea of a Customs Union within the EAEC in 2010. This year, the Common Economic Area (CEA) was established with the aim of setting a basis for an eventual transition to a Eurasian Economic Union. Ukraine and Moldova are simply interested in free trade with CIS countries and choose not to participate in economic and political integration.

The Asian dimension, and especially relations with China, has become increasingly important in Belarusian and Ukrainian foreign policies over the last few years. So, Minsk and Kyiv hope that partnerships in Central Asia will provide them with greater involvement in regional organisations in Asia. For example, with Kazakhstan’s support, Belarus joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) as a partner for dialogue and is seeking participation in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation. Belarus also cooperates with Central Asian countries within such fora as the UN and the OSCE, particularly in opposing the democratisation efforts of the Western states. When it faced EU and US sanctions, Belarus made sure it received declarations of support from the Customs Union, the CSTO and the EAEC. In 2010, Belarus promoted Kazakhstan (as well as Russia) as a friend of the EU’s Eastern Partnership. Kyiv is also keen on cooperating with the SCO. Ukraine has observer status at the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia, a Kazakhstan-led initiative that involves Asian and Middle Eastern countries as well as Russia and Turkey.

Belarus has embassies in all five Central Asian capitals. Ukraine has established a diplomatic presence in all of the countries except for Tajikistan, which is covered from Ukraine’s embassy in Uzbekistan. All of the Central Asian countries have diplomatic presence in Belarus and Ukraine, expect for Uzbekistan, which covers Belarus from its embassy in Moscow. Moldova has no embassies in Central Asia and no Central Asian state has an embassy in Chisinau. Kazakhstan’s ambassador in Kyiv is also the ambassador for Moldova. Relations between Moldova and Central Asia are of low priority for both sides. Moldovan and Central Asian leaders regularly meet within the CIS summits, but no high-level visits between Chisinau and Central Asian capitals have occurred in the last several years. The only major exception was the visit by Kazakhstan’s foreign minister to Chisinau and Tiraspol during Kazakhstan’s OSCE presidency in 2010.

Bilateral relations with Kazakhstan are the most developed for all of the East European countries, because of Kazakhstan’s importance as a trade partner for Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine, along with its increasingly significant political role. Belarus and Kazakhstan are strategic partners and top-level bilateral contact has intensified since the formation of the Customs Union. Alongside regular multilateral meetings, Kazakhstan’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, paid an official visit to Belarus in 2009 and 2012. Belarus’s president, Alexander Lukashenko, visited Kazakhstan in 2011. Minsk is eager to use the alliance with Astana to offset Russia’s economic and political influence within the CEA.

Belarus-Turkmenistan relations are growing. President Lukashenko visited Turkmenistan in 2009 and 2011 and Turkmenistan’s president, Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov, paid visits to Belarus in 2010 and in April 2012. Contacts with Tajikistan have deepened over the past year: in 2011, Belarus opened its embassy in Dushanbe and Lukashenko paid an official visit to Tajikistan.

Since the new government took over in Bishkek in 2010, Belarus-Kyrgyzstan relations have been tense. Lukashenko fiercely opposed the regime change in Bishkek, fearing that it might be repeated in Belarus. He criticised the CSTO (and implicitly, Moscow) for not intervening in the Kyrgyzstan political crisis. And he granted asylum to the ousted president, Kurmanbek Bakiev, who was not popular with the Kremlin.

Belarus’s relations with Uzbekistan are less developed. The Uzbek president, Islam Karimov, reportedly has a bad relationship with Lukashenko, and foreign policy in both countries relies to a great extent on personalities and feelings, to the detriment of any other interests. In 2011, the Belarusian president more than once suggested excluding Uzbekistan from the CSTO for playing a ‘triple game’ and for not ratifying CSTO documents.

Among the Central Asian countries, Turkmenistan has always been of special importance to Ukraine, since the country was a major gas supplier to Ukraine until 2006. Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych’s government has revitalised relations with Ashgabat, launching a number of visits by high-level delegations in 2010-2011, and in 2011 Yanukovych paid an official visit to Turkmenistan. In March 2012, Turkmenistan’s president paid a state visit to Ukraine, the first in ten years. During his stay, a number of bilateral documents were signed, including a programme for trade and economic cooperation.

Relations between Kyiv and Astana are well developed. President Yanukovych’s first official visit abroad in 2010 was to Kazakhstan, and he has visited Kazakhstan on two other occasions since then. President Nazarbaev travelled to Ukraine twice in 2010 and once in 2011, for the Kyiv summit on nuclear energy.

Ties with Uzbekistan stagnated after the Orange revolution of 2004 and the events in Andijan in 2005, which moved Uzbekistan away from cooperation with the West and renewed its ties with Moscow. Yanukovych’s government is keen on reviving the close relations with Tashkent that Ukraine enjoyed during the Kuchma era. Ukraine’s foreign affairs minister paid an official visit to Tashkent this year and met with President Karimov.

Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan receive less political attention from Ukraine. Kyiv and Dushanbe exchanged presidential visits in 2008, and in 2011 Tajikistan’s president, Emomalii Rakhmon, paid an official visit to Ukraine. Former president Viktor Yushchenko supported the Kyrgyz ‘Tulip revolution’ in 2005 and a large Ukrainian delegation attended President Bakiev’s inauguration. However, high-level contacts since then have been limited, with the exception of 2007 when a large Ukrainian delegation visited Bishkek for Ukraine’s WTO accession talks.

Trade and Investment

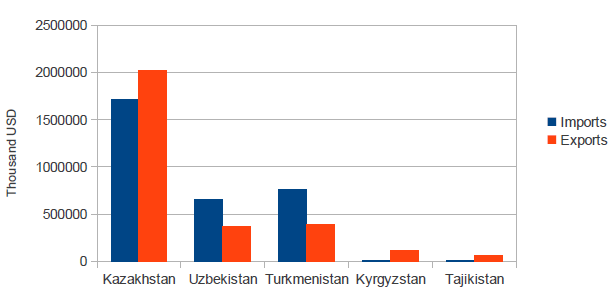

All three East European countries have significant trade with the CIS countries. CIS trade accounts for 35 per cent of Moldova’s foreign trade and 57 per cent of Belarus. Among the CIS countries, Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine trade mainly with Russia and each other. Trade with Central Asia is less important, with the exception of trade with Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is the third biggest CIS trade partner for Belarus and Ukraine and the fourth biggest for Moldova, after Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. Kazakhstan’s importance out of all trade partners ranges from sixth to ninth for the three Eastern European countries. Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan follow, but they are considerably less important to the foreign trade of the Eastern European countries. Trade volumes with Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan are small.

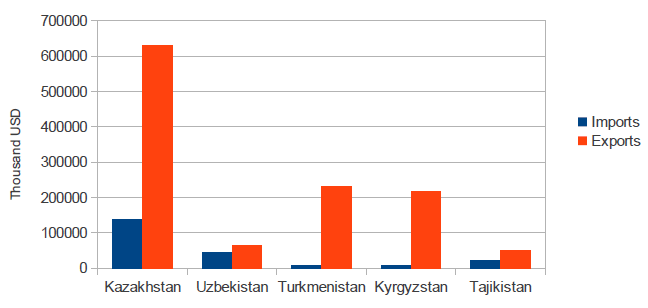

Belarus has a surplus in its trade with Central Asia. This helps Minsk to tackle its $5.5 billion foreign trade deficit, existing in great part due to its negative trade balance with Russia, which reached $11.2 billion in 2011. Belarus mostly exports ‘technology’ products to Central Asia: vehicles, tyres, agricultural machinery and refrigerators, as well as food and medicines. Imports to Belarus include black metals, minerals and chemicals from Kazakhstan, and spare parts, agricultural products and textiles from the other republics. Belarus does not import energy from Central Asia, although it provides transit to Europe for Kazakhstan’s oil. Membership in the Customs Union seems to have had a positive effect on the growth of Belarusian exports and on the establishment of Belarusian economic activity in Kazakhstan.

Source: http://belstat.gov.by

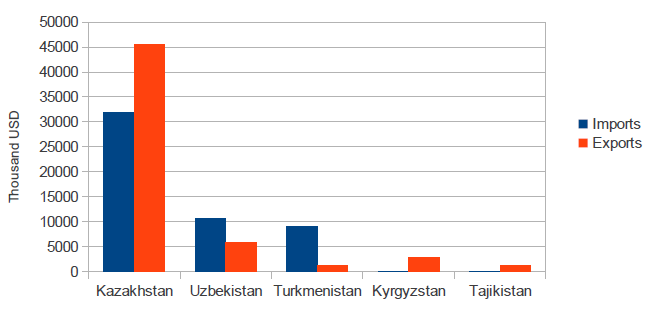

Ukraine imports more than it exports from Central Asia. Energy accounts for about ninety per cent of Central Asian imports to Ukraine. Ukraine exports metallurgy production, agricultural goods, machinery and chemicals. Ukrainian firms are involved in projects to build transport and energy infrastructure in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. For example, Ukrainian companies sold pipes and provided services for the East-West pipeline connecting gas fields in east Turkmenistan with the Caspian shore.

Source: http://www.statistica.md. This chart does not include export-import operations of Transnistria.

Moldova’s trade with Central Asia is insignificant. Trade with Kazakhstan, the most important of Moldova’s Central Asian trade partners, makes up less than one per cent of Moldova’s foreign trade. In general, Moldova’s trade with post-Soviet countries has decreased since early 2000, while trade with the EU has increased as a result of preferential trade regimes.

Source: www.ukrstat.gov.ua

Investments between Eastern Europe and Central Asia are not substantial. Kazakhstan is one of the countries that receives most Ukrainian investment, but it has gained only $25 million from Ukraine in 2012. Most Central Asian investment in Eastern Europe comes from Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan’s BTA bank operates in Belarus and Ukraine. Astana expects to increase its investment in Belarus to help with the implementation of common projects on infrastructure and transit of Kazakhstan’s oil to Europe. As a check to the growing economic expansion of Russia, Belarus offered Kazakhstan the opportunity to buy the state’s share in MTS, the main mobile operator in Belarus.

Energy

Central Asia is an important region for Ukraine’s energy security plans. In the past, Turkmenistan was Ukraine’s largest energy supplier. But since 2006, Central Asian gas has been delivered to Ukraine by Russia’s Gazprom, because of bilateral contracts between Russia and Ukraine.

Kyiv is interested in renewing direct deliveries from Central Asia, but Russia does not want to give up its transit monopoly. Tymoshenko’s government promoted the White Stream pipeline project to bring Caspian gas through Georgia and the Black Sea to Ukraine and on to Europe. However, the EU did not support the plan. Recently, the Ukrainian government expressed its interest in participating in the Trans-Caspian pipeline. This pipeline, if completed, would bring gas from Turkmenistan and potentially other Central Asian countries to Azerbaijan and on to Europe through one of the routes under consideration for the EU’s Southern Energy Corridor. Kyiv also plans to build an LNG terminal at the Black Sea and hopes that Kazakhstan, among other gas-rich Caspian states, will participate. But the future of these projects is unclear due to uncertainty about suppliers and investors. Competition for Central Asian gas is growing, with China and potentially India and Pakistan vying for a share, and Ukraine fears that its chances to obtain Central Asian gas are waning.

Kyiv is also counting on Caspian oil to develop its oil industry. In the 1990s, in order to lessen its dependence on Russia, Ukraine built the Odessa-Brody pipeline along with a terminal near Odessa to bypass Russia in bringing Caspian oil to Ukrainian refineries. But their capacities are largely underused. Kyiv hopes to increase oil supplies from Azerbaijan, following the 2011 agreement on transit of Azerbaijani oil to Europe through Ukraine, as well as from Kazakhstan, from which oil transit was suspended in 2010 when Ukraine increased transit tariffs. Ukraine also wants to attract investment for the modernisation of its oil processing industries.

Belarus has a long-standing interest in using Kazakhstani oil to reduce its reliance on Russia. After Russia introduced oil export duties that threatened the basis of Lukashenko’s economy, Belarus in 2010 negotiated oil shipments from Venezuela. Belarus also gets oil from Azerbaijan through Ukraine’s Odessa-Brody pipeline. But the amounts received are small and more expensive in comparison to Russian imports.

As an oil exporter, Kazakhstan is interested in oil processing and has a clear desire to acquire stakes in Belarusian oil refineries. Minsk is keen on cooperation with Astana, because it needs money to modernise its oil industry. Besides, Belarus would prefer Kazakhstan to own its refineries rather than Russia, because of its fear of further Russian economic expansion. However, once more, the key to Belarus-Kazakhstan energy cooperation lies in Russia, since Russia controls the transit pipelines and is not eager to give up a useful tool for applying pressure on both Belarus and Kazakhstan.

Security cooperation

Belarus and all of the Central Asian countries aside from Turkmenistan are members of the Russia-led CSTO, which was created in 1992. In 2009, the CSTO Collective Rapid Reaction Force was established, with the participation of all the CSTO members apart from Uzbekistan. Within this framework, annual military exercises are carried out. The member states cooperate on military training and development and on maintenance and repairs of military equipment. They work together on issues like the fight against terrorism, transnational organised crime, drug smuggling, and natural and man-made disasters.

Moldova and Ukraine are self-declared neutral countries, so they have no interest in joining any military unions, including the CSTO. Bilateral military cooperation is developing between Ukraine and Kazakhstan. There are plans to establish a common enterprise in Kazakhstan to repair outdated military equipment. In President Kuchma’s time, Ukraine sold and repaired weapons and military equipment for Ashgabat. But this cooperation has since shrunk, although it remains on the agenda of bilateral cooperation.

The post-Soviet countries are all members of the NATO’s Partnership for Peace programme. Ukraine contributes to the International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan, providing transport aviation services and 22 peacekeepers. This year, Ukraine will provide instructors for the NATO-Russia Council project on training anti-drug specialists for Central Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Unlike the EU, Russia and the U.S., Eastern Europe is not particularly interested in debating the security risks of NATO’s withdrawal from Afghanistan over the coming two years and how it might affect stability and security in Central Asia. In Kyiv, the main debates are focused on Russia and the EU rather than on other regions, regardless of potential security threats that could cause setbacks for Ukraine’s economic and energy interests.

People-to-people contacts

People-to-people contacts are facilitated by visa-free travel regimes between the East European and Central Asian countries, aside from Turkmenistan. Direct flights operate between Kyiv and Bishkek, Dushanbe and Tashkent, as well as three cities in Kazakhstan. From Minsk, flights go to Ashgabat, Astana and three other Kazakhstani cities. However, tourism between the regions is underdeveloped. East European diasporas still form part of the population of Central Asian countries, with the most numerous community being about half a million Ukrainian descendants in Kazakhstan. But diasporas play almost no political role in relations between the countries.

Turkmen students are the largest foreign student group in Belarus and the second largest in Ukraine – around 4,500 study in Belarus and 5,500 in Ukraine. Cooperation programmes exist between universities in Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan is keen on importing teaching by inviting foreign academics, including ones from Eastern Europe, to its universities. There are few contacts between civil society groups in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. NGOs and think tanks mainly meet in broader fora organised through, for example, the OSCE.

The post-Soviet countries tend to provide each other humanitarian aid in emergency situations. Belarus receives credits from the EAEC anti-crisis fund established in 2009, which is also sponsored by Kazakhstan.

Conclusion

The East European countries’ policies towards Central Asia have developed within the framework of post-Soviet reintegration. Belarus has the most intensive network of contacts with Central Asian regimes, due to shared membership in regional organisations such as the CSTO, the EAEC and the Customs Union. Ukraine has built strong bilateral relations with Central Asian states in order to ensure its energy security. Moldova’s relations with Central Asia are the least developed.

In spite of the numerous political, economic, security and human ties that exist between the two regions, Central Asia is not one of the East European countries’ first priorities in foreign policy. The best diplomats are sent to Russia, Europe and the U.S., and think tanks and research institutes in Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine rarely publish anything on their countries’ interests in Central Asia. The Central Asian dimension is usually promoted when Minsk or Kyiv are under too much pressure from Moscow, but Russia remains a major challenge to the development of relationships between the two regions.

Meanwhile, the common post-Soviet past is becoming of less value in developing policies towards Central Asia. Smaller East European states have to manoeuvre between the interests of the great powers in the region. The example of Ukraine, which seeks to join European energy projects in Central Asia, is illustrative. On the one hand, Ukraine hopes to benefit from potential energy routes between Central Asia and Europe. But on the other hand, it fears losing even an elusive prospect of getting Caspian gas, which is more likely to flow to China or Western Europe than to Ukraine.

Central Asia continues to be an important arena for the realisation of the economic and energy interests of the Eastern European states. But any increase in economic transactions between the two geographically distant regions depends on new transport and energy corridors that cannot be built without the involvement of bigger actors such as Russia and Europe. In the future, Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine may feel even more pressure to align their priorities in Central Asia with those of their patrons.

Download “European National Policies Series - Eastern Europe and Central Asia”

EUCAM-National-Policies-Series-3.pdf – Downloaded 330 times – 1.36 MB