European National Policies Series – The South Caucasus and Central Asia

Download “European National Policies Series - The South Caucasus and Central Asia”

Twenty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the countries of the South Caucasus and Central Asia have developed relations within multilateral regional organisations as well as on a bilateral basis. Azerbaijan’s bilateral relations with Central Asian countries are centred on energy, transport routes and trade. Georgia sees Central Asia as important in strengthening its energy security and in diversifying foreign investments. Armenia’s bilateral contacts with Central Asian countries are limited.

Central Asia is not a major foreign policy target for Caucasus countries. Baku, Tbilisi and Yerevan are mostly focused on cooperation with Brussels, Washington and Moscow. The EU, the U.S. and Russia are essential to the economies of the South Caucasus countries and play an influential role in the unresolved conflicts in Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh. The security problems and low level of development of the South Caucasus countries have left little space so far for constructive engagement beyond direct neighbours and influential powers.

Political relations

Alongside bilateral engagements, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia have contact with Central Asian countries in post-Soviet regional cooperation platforms as well as within western-backed international organisations. Central Asian countries tend to be more closely affiliated with Russian-driven post-Soviet regional organisations, but in the South Caucasus, participation in these fora is more asymmetrical.

Apart from Georgia, all the countries of both the South Caucasus and Central Asia are members of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Since 2009, Georgia has opted out from all Russian-led regional cooperation organisations. Of the South Caucasus countries, only Armenia participates in the CIS Free Trade Area and the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO). All the Central Asian countries apart from Turkmenistan are members of these groups, although Uzbekistan has recently declared its intention to withdraw from the CSTO. None of the Caucasus countries have expressed interest in being part of the Moscow-led Customs Union, established in 2007, or in its next step of integration, the Common Economic Area, set to come into force in 2012. Azerbaijan is a member of the Organisation for Islamic Cooperation (IOC), along with all five countries of Central Asia.

Countries in the South Caucasus and Central Asia participate in the EU-backed ‘Basic Multilateral Agreement on International Transport for Development of the Europe-the Caucasus-Asia Corridor’ (TRACECA). This initiative aims to build infrastructure to revive the ancient Silk Road and link the countries of the region with world markets. TRACECA is supported through the Baku Initiative, which seeks to facilitate cooperation between the EU, the littoral states of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea, and their neighbours, so as to ensure consistency with the EU’s neighbourhood policy.

Azerbaijan has embassies in all the Central Asian countries except Tajikistan and it also has a consulate in the western Kazakhstan city of Aktau. Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan have embassies in Baku. Georgia has ambassadors in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. The Kazakhstan embassy covers Kyrgyzstan, the embassy in Uzbekistan has responsibility for Tajikistan, and the Turkmenistan mission also covers Afghanistan. Of the Central Asian countries, only Kazakhstan has an embassy in Tbilisi. Kyrgyzstan’s Moscow embassy also covers Georgia and its embassy in Baku covers Uzbekistan. Armenia has representation in Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, and both countries likewise have diplomatic missions in Yerevan.

Kazakhstan is the most important bilateral partner with the countries of South Caucasus, because of its economic weight and its role in energy provision. In terms of trade volumes, Turkmenistan is the second most important partner for the Caucasus countries. Because of longstanding cultural and historic linkages, Kazakhstan has special ‘fraternal’ relations with Azerbaijan, so the two countries consider themselves to be the main allies connecting Central Asia and the Caucasus. Georgia is increasing in importance to Kazakhstan since it provides potential access to the Black Sea, along with a favourable investment climate. Armenia is the country most integrated in the Moscow-led regional organisations that unite the Central Asian countries. But these multilateral connections do not seem to have much impact on its bilateral political, trade and energy relations with the countries of Central Asia.

In 2011, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan upgraded their bilateral relations to a strategic partnership. Regular high-level visits take place between both sides, and the main areas of cooperation between the two are energy, transit routes and trade. After a gap of six years, Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan held their first high-level political meeting in 2010. During the visit of Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev to Uzbekistan, the heads of states of both countries pledged to support each other on regional security issues. Uzbekistan failed to obtain support from the US and NATO for its ‘6+3’ solution for Afghanistan, so it is trying to gain backing from regional players, including Baku. In spite of progress on regional security issues, trade between Azerbaijan and Uzbekistan remains marginal.

Disputes over Azerbaijani gas debt and divisions over the Caspian seabed seriously damaged relations between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan in the first decade of the century. Relations between the two countries were non-existent between 2001 and 2006, after Turkmenistan recalled its ambassador from Baku in 2001. Rapprochement between the two countries has begun since Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov came to power in Turkmenistan in 2006. The Azerbaijani debt issue was resolved in 2008 after Baku agreed to pay Turkmenistan $44.8 million. However, relations remain tense, mostly due to disputes over oil fields and the division of the Caspian seabed. The ongoing dispute over the Kapaz oil field (Serdar in Turkmen) resurfaced in 2012, when seismic work on the Turkmen side caused outrage from Azerbaijani authorities. Azerbaijan said the work violated a 2008 agreement that stipulates no exploitation work should be carried out in the field until the disagreement over the Caspian seabed is resolved.

Relations between Georgia and Uzbekistan are driven by economic interests. In 2012, the Georgian-Uzbek trade-economic cooperation commission resumed work after almost nine years of inactivity. This development will help Georgia in facilitating the Silk Road transport route and infrastructure diversification project, as well as encouraging cooperation with Uzbekistan within the TRACECA project. In 2005, Georgian Prime Minister Zurab Noghaideli visited Uzbekistan, and since then, a few other visits have taken place between the two countries at ministerial level.

Kazakhstan has become more important to Georgia in recent years. Georgia hopes to obtain gas from Kazakhstan and supports the construction of a Trans-Caspian gas pipeline to transport gas to European markets. In return, it can provide Kazakhstan with access to its Black Sea grain and oil terminals, as well as offering a favourable investment climate for Kazakhstani businesses. The intergovernmental commission for trade and economic cooperation between the two countries meets regularly. High-level visits between both sides took place in 2010.

Engagements between Georgia and Turkmenistan revolve around energy. Since 1993, Georgia has sent eight high-level missions to Ashgabat, headed by the President and other high-ranking officials. Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili’s last visit to Ashgabat was in 2007. Visits from Turkmen officials to Tbilisi are less frequent: only two high-level visits have taken place, the most recent being the visit of Turkmenistan’s Speaker of Parliament, Akja Nurberdyev, in 2008. Georgia hopes that the construction of the Trans-Caspian Pipeline would help secure a share of Turkmenistan’s natural gas for Georgia.

Georgia paid close attention to the regime changes in Kyrgyzstan in 2005 and 2010. After the 2005 ‘Tulip Revolution’ in Kyrgyzstan, President Saakashvili, along with Ukraine’s president, Victor Yushchenko, addressed a letter to the Kyrgyz people that called for ‘a legitimate constitutional way out of the crisis’. Both countries sent their foreign ministers to the country during the crisis and announced their ‘readiness for mediating at the talks between ex-President Askar Akayev and the representatives of the interim government.’ During the June 2010 ethnic violence in Kyrgyzstan, the Georgian state minister for reintegration, Temur Iakobashvili, called the events ‘Russian-inspired “ethnic cleansing” of Uzbeks’. Under both governments, Kyrgyzstan has maintained good neighbourly relations with Georgia. Both Georgia in the South Caucasus and Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia tend to have the most support for the Western democratic model as compared to their neighbours. The frequent visits of Kyrgyz politicians to Tbilisi are focused on learning from Georgia’s experience of police reform and anti-corruption policies.

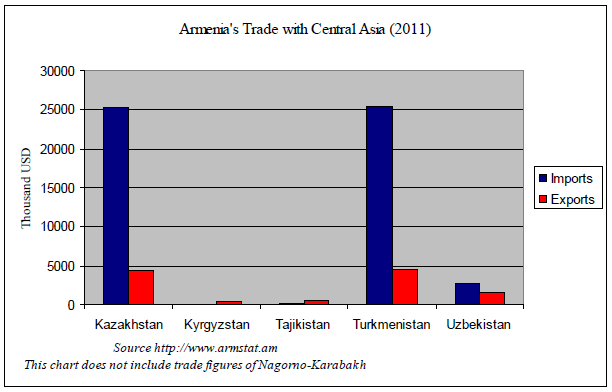

Armenia has limited bilateral relations with Central Asian countries. It maintains a regular political dialogue with Kazakhstan, but trade and economic relations are insignificant. Armenia’s relations with other Central Asian countries take place within the framework of CIS and CSTO platforms.

Trade and Investment

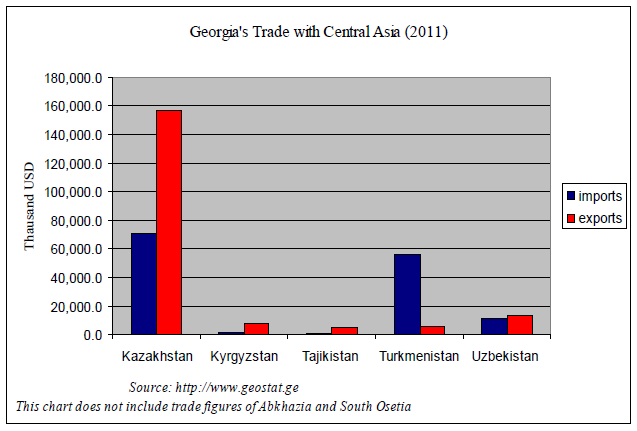

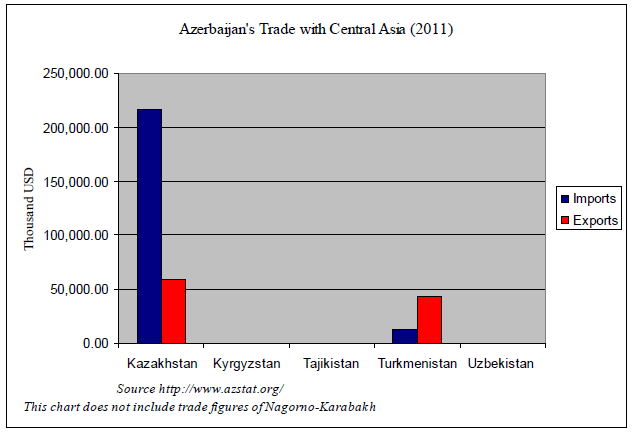

Trade between the two regions is mostly dominated by energy and its transit to western markets. The countries of the two regions are not among each other’s top trade partners.

Georgia’s top three trade partners in 2010 and 2011 were Turkey, Azerbaijan and Ukraine. In 2010, Kazakhstan was its tenth most important trade partner. In 2011, none of the Central Asian countries were among the top ten. Kazakhstan remains the leading Central Asian trade and investment partner for Georgia. Georgia’s imports in Kazakhstan increased in 2011, as did Kazakh investments in Georgia. Most Kazakh investments in Georgia are in banking, construction, energy and tourism. Kazakhstan has invested in the construction of some hotels in Tbilisi and in the development of tourism in the Adjara region. In 2006, KazTransGaz purchased TbilisiGas (now KazTransGaz-Tbilisi), and has operated the company since then. After the acquisition, KazTransGas renovated TbilisiGas’s outdated infrastructure and pipelines, with a total investment of $79.3 million. Kazakhstani companies also invested in an oil terminal in the Black Sea city of Batumi. Georgia is attempting to attract Kazakh investment for the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway. Georgia wants to be a transit country for Kazakh grain to third countries through the Black Sea port of Poti. Rehabilitation of the existing grain terminal in Poti was completed last year and a second grain terminal is set to begin operations this year.

In 2010, Azerbaijan’s top three trade partners were the United States, Russia and Israel. In 2011, of the Central Asian countries, only Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are in Azerbaijan’s top 20 trade partners, placed 20th and 24th respectively. Kazakhstan exports grain, oil and related equipment to Azerbaijan.

Armenia’s top three trade partners in 2010 were Russia, China, and Iran. Armenia’s isolation and closed borders with two out of its four neighbouring countries has implications for its trade with Central Asian countries. Its most important Central Asian trade partners are Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Armenia imports raw materials such as metals from Kazakhstan and exports commodities such as footwear. From Turkmenistan, Armenia imports raw materials and knitted garments, while it exports some luxury goods such as jewels and gemstones.

Energy

Countries in the Caucasus and Central Asia can be divided into energy-rich countries (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan), transit countries (Uzbekistan, Georgia and in future Azerbaijan), and countries with no involvement in either energy production or transit (Armenia, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan). Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan share Caspian Sea energy reserves with Russia and Iran. Azerbaijan’s state oil company, SOCAR, cooperates closely with Kazakhstan’s KazMunaiGas to deliver Kazakhstani oil to the world market through Azerbaijan.

One of the EU’s interests in Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan concerns the uncertain Trans-Caspian pipeline project, part of the Southern Gas Corridor project which is included in the ‘Silk Road’ transport and energy strategy. In September 2011, the European Council gave a mandate to the European Commission to start negotiating a legally binding treaty on the construction of the pipeline between Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and the EU. During his visit to Astana in autumn 2011, European Commissioner for Energy Günther Oettinger invited Kazakhstan to join the project. Moscow is opposing the Trans-Caspian Pipeline, claiming that it will have a negative environmental impact and insisting that any pipeline should be approved by all five littoral Caspian Sea states. Russia wants to build an alternative South Stream pipeline, which would deliver almost the same volumes of gas to European markets.

The unresolved status of the Caspian Sea precludes any certainty on future infrastructure projects. The littoral states have so far failed to agree on the division of Caspian Sea resources into ‘national economic zones and sectors’. Summits in Ashgabat in 2001 and Tehran in 2007 yielded no concrete results, and to date, no concrete agreement has been put in place. Some bilateral agreements exist between Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Russia, but Iran and Turkmenistan consider those agreements invalid.

The three unresolved conflicts in the Caucasus pose a potential threat to the current pipelines transporting oil and gas from Azerbaijan through Georgia to Turkey, which could in future also convey Central Asian energy. No pipelines were bombed during the five-day war between Georgia and Russia in August 2008, but the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline’s operation was halted that month due to a blast for which the Kurdish PKK claimed responsibility. Energy transport infrastructure would be particularly vulnerable in the event of hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Security

Security threats in the South Caucasus are primarily associated with the three unresolved conflicts in the region. None of the CIS countries have joined Russia in recognising the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Four of the Central Asian states made cautious statements on recognition, while Turkmenistan maintains its neutrality. Kazakhstan justified its official position on non-recognition by pointing to the fact that it has also refused to recognise Kosovo. Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan said they would need to take time to measure the situation. Tajik President Emomali Rahmonov expressed support for the Russian decision to recognise the breakaway regions, but did not translate this support into official recognition.

Nonetheless, some defence cooperation between both regions is developing. In 2011, the Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan defence ministers approved a military cooperation plan that covers the modernisation and purchase of military equipment. It also provides for cooperation between naval forces, including information exchange on hydrography and joint navigation of vessels in the Caspian Sea. In 2010, Azerbaijan agreed bilateral military cooperation plans with Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan. Georgia and Armenia are not involved in bilateral military cooperation with Central Asian countries. Armenia cooperates militarily with Central Asia via CSTO structures, while Georgia’s priority is Euro-Atlantic integration.

All countries in both regions participate in the NATO Partnership for Peace (PfP) – although with varying levels of enthusiasm. Cooperation between NATO and South Caucasus countries is more developed than between NATO and Central Asian countries. But PfP exercises and the Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council offer opportunities for both regions to discuss defence matters with NATO and with each other.

Georgia is a major non-NATO contributor to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan. It has 925 troops in Afghanistan, of which 750 are in Helmand province and 175 in Kabul. In 2012, Georgia plans to send an additional 749 soldiers to Afghanistan. Despite this large peacekeeping contribution to ISAF, as the 2014 deadline for withdrawal approaches, Georgia has little involvement in the continuing discussions on the potential threats of spill-over from Afghanistan into Central Asia, and the issue is not the subject of much debate at home.

People-to-people contacts

Citizens of the South Caucasus and Central Asian enjoy visa-free travel with each other, with the exception of Turkmenistan. However, there are few direct flights between the countries. There are no direct flights from Yerevan to any Central Asian cities. From Tbilisi, there are direct flights to several cities in Kazakhstan as well as to Bishkek. Baku has direct air connections with a number of cities in Kazakhstan and with Tashkent.

In 2012, Georgia and Kazakhstan signed a bilateral agreement on tourism cooperation. Kazakhstan invested substantially in Georgia’s Black Sea resort, Batumi. Georgian tourism figures rose steeply in 2011 but it is uncertain if this includes increased numbers of Kazakh tourists. But the elites of both regions in general prefer to visit western and Middle Eastern destinations.

The Armenian diaspora in Kazakhstan is estimated to number between 25,000 and 100,000 people and around 70,000 Armenians live in Uzbekistan. This has had no significant impact on relations with Armenia. Unlike the Armenian diaspora in the U.S. and in France, Armenians in Central Asia do not play much part in lobbying for their country’s interests.

Academic and civil society exchanges are limited and not well recorded. The OSCE has created some links between civil society organisations from both regions and some European and American initiatives also provide opportunities for exchange. Former Soviet linkages seem largely to have evaporated.

Conclusion

In the early nineties, relations between the South Caucasus and Central Asian countries were mostly dominated by post-Soviet reintegration. But today, post-Soviet organisations seem less important in fostering bilateral links. Georgia and Azerbaijan have relatively strong bilateral relations with Central Asian countries. Armenia, although it is much more closely integrated in post-Soviet regional organisations, has little bilateral cooperation with the region.

The geographical proximity of the two regions is important in current and planned transport and energy infrastructure projects. Both energy-rich and energy-poor countries have a shared interest in lessening Russian dominance in energy transit and supplies. So, energy and economic cooperation is high on the agenda of bilateral relations between the countries.

Regional integration between the South Caucasus and Central Asian countries seems mostly of interest to third parties rather than to the countries themselves. Russia has formed a number of post-Soviet reintegration platforms, but these organisations have not brought the countries closer together, nor have they boosted trade or improved the security situation in the region at large.

The EU is another third party that sometimes seeks to link the Caucasus and Central Asia regions. But its envisaged connections are mostly in the sphere of energy cooperation and infrastructure, such as transport corridors. European Silk Road thinking clearly connects Central Asia to Europe, with the Caucasus in the centre. But ultimately, for the EU, the South Caucasus is part of its perceived neighbourhood and Central Asia is not. Meanwhile, the U.S. has proposed its own ‘New Silk Road’ aimed at linking Central Asia with South Asia, so as to help the Afghanistan transition process by developing trade. These two external visions do not necessarily have to be at odds. But if Central Asia’s regional integration leans towards South Asia and the South Caucasus is integrating with the West, it is questionable just how viable Central Asia-South Caucasus regional projects really are.

Download “European National Policies Series - The South Caucasus and Central Asia”

EUCAM-National-Policies-Series-4.pdf – Downloaded 391 times – 1.22 MB