Trading values with Kazakhstan

Download “Trading values with Kazakhstan”

EUCAM-Policy-Brief-32.pdf – Downloaded 431 times – 774.27 KBThe European Union (EU) and Kazakhstan have become important partners over the past decade. The EU is Kazakhstan’s leading trade partner, accounting for 40 per cent of its exports. At the same time, Kazakhstan contributes to meeting the EU’s oil and uranium demand and Europe is increasingly interested in the country’s extensive natural resources. Growing economic and political ties have brought EU-Kazakhstan relations to a new level that seems to surpass the current bilateral agreement and the overarching (regional) engagement through the EU Strategy for Central Asia. In 2011, negotiations began over a new and enhanced agreement to replace the current Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA). Despite substantial initial progress, recently talks have slowed down. Kazakhstan’s interest seems to be declining and differences are mounting over two key issues: technical and regulatory aspects related to trade and investment, and a clearer commitment and results by Astana towards democratic reform.

Whereas Kazakhstan has managed to boost its image abroad, concerns abound over the country’s performance in terms of democracy, human rights, rule of law and good governance at home. The Kazakh government’s commitments in the run-up to the 2010 chairmanship of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) seemed to indicate a willingness to reform and modernise existing institutional structures, but few results have been recorded to date. The launch of a National Human Rights Action Plan in 2009 has not brought about change; in fact, over the last few years Kazakhstan has introduced restrictive policies regarding national security, religious freedom and the Internet.

Kazakhstan seems merely to be piling up commitments while stalling on actual reform. The authorities’ crackdown on oil workers’ demonstrations in Zhanaozen in December 2011, followed by the arrest of opposition leaders and the closing of several media outlets, has further highlighted Kazakhstan’s unwillingness to advance on political reform. This raises questions about the country’s democratic commitments and its stated intention to move closer to Europe, which was reiterated in November 2011 when the Council of Europe approved Kazakhstan’s membership of the Venice Commission.

As European Commission President José Manuel Barroso mentioned during his visit to Astana in June 2013, Europe is looking for a politically stable partner in Central Asia. While Kazakhstan has advanced economically and is considered more stable than some of its neighbours, its stability is based on a ‘strong man’ rather than on democratic governance, rule of law and respect for human rights. As a normative actor, the EU promotes these principles in its relations with partner countries. However, in dealings with resource-rich states the Union tends to shy away from its normative agenda. This does not have to be the case with Kazakhstan. The Central Asian state presents trade and investment opportunities for Europe, but the Union is also a vital market and source of technology for the country. Kazakhstan’s economic and political success will largely depend on the country securing an alternative to trade and ties with Russia and China. A clear EU stance on Kazakhstan’s democratic and human rights commitments would be mutually-beneficial: political stability rooted in democratic principles would strengthen the country’s profile on the global stage, while the EU would gain a more reliable partner.

An enhanced relationship?

The EU-Kazakhstan Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) has been in force since 1999. It has a ten-year tenure and is automatically renewable. In the mid and late 1990s, the EU signed similar agreements with most post-Soviet states. These accords provide a legal framework(1) for economic cooperation between these countries and the EU and its member states, covering issues such as trade, business and investment, and legislative and financial cooperation. Under a PCA, the parties grant each other most-favoured-nation status,(2) which guarantees favourable customs duties and charges on imports and exports. Since almost half of Kazakhstan’s exports go to the EU, the most-favoured-nation clause is essential for Astana.

Political dialogue is a small but integral part of the PCA. Annual meetings are held in Brussels within the framework of the high-level Cooperation Council. The Council’s last gathering in July 2013 stressed political reform, trade, and regional security and cooperation but did not bring about ground-breaking decisions or initiatives. While the existing PCA also includes standard commitments by the parties towards the rule of law and human rights, it does not include specific issues, actions or a timeline. For example, the annual Human Rights Dialogues between the EU and Kazakhstan were established only after the 2007 EU-Central Asia Strategy for a New Partnership came into effect and are not part of the current PCA.

After several requests from the Kazakh government to launch negotiations on a new agreement, the 2009 Cooperation Council concluded that the existing PCA did not reflect the extent of the cooperation between the parties and agreed on the need to reach a new agreement.(3) In 2011, the European External Action Service (EEAS) began negotiations with Kazakhstan on an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement. The third round of talks took place in July 2012 in Astana, and the fourth round is scheduled for October 2013.

A new PCA is not legally required. Negotiations have been launched on the basis that both partners have changed and that the relationship has reached a new level. The EU’s relations with the other Central Asian states continue to be regulated through the initial agreements. This emphasises Kazakhstan’s special status and fits with Astana’s aspirations to play a greater international role and build strong ties with key global players. For the EU, negotiations will only make a positive difference if stronger prescriptions for reform are envisaged and progress is made on Kazakhstan’s accession to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). The latter would bring Kazakhstan closer to the EU in terms of trade and investment-related regulations and standards. The EU’s and its member states’ economic and trade interests are already largely accommodated in the current PCA. Thus, a new agreement has to go further, notably paving the way for progress towards democratic reform, which would help increase Kazakhstan’s stability and thus protect European investment in the long-term. But talks are taking place behind closed doors and it is still not clear how a new PCA would differ from the current one.

Building on trade and investment

For the EU, ‘enhancing’ the partnership would lie largely in building stronger political ties and fostering democratic governance in Kazakhstan, which would in turn result in longer- term stability and development. Meanwhile, Kazakhstan seeks international recognition but above all better access to the European market.

Regardless of China and Russia’s vicinity, the EU is Kazakhstan’s leading trade partner and offers a market of over 500 million people. In recent years, Europe has accounted for almost half of Kazakhstan’s foreign direct investment (FDI). Next to providing a continuous cash-flow, Europe is also an important partner when it comes to sharing know-how, expertise and technology. According to data from the European Commission, in 2012 EU exports to Kazakhstan were worth €7.1 billion, while the country’s exports to the EU amounted to €20.1 billion.

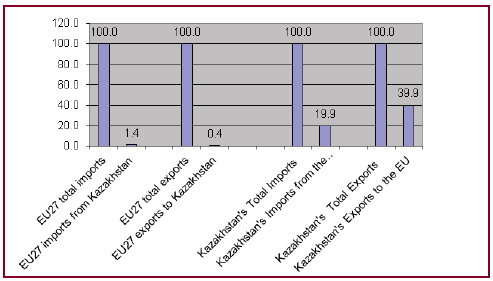

Kazakhstan’s share (in percentages) in the EU’s exports-imports and the EU’s share in Kazakhstan’s exports-imports in 2012.

*Figures from the European Commission DG Trade.

Fuels and mining products represent over 90 per cent of Kazakhstan’s exports to the EU. Over the last seven years, Kazakhstan’s share of EU oil imports stood at around 5 per cent,(4) whereas the EU absorbed over 70 per cent of Kazakhstan’s oil exports.(5) While oil imports from Kazakhstan are substantial, the EU’s dependence on Kazakh oil overall remains limited. EU member states such as Germany and France have struck deals with Kazakhstan with a view to exploiting and importing rare earths. Kazakhstan has important reserves of fossil fuels and rare earths but needs to attract technology and investment to exploit them and markets for its exports. Above all, it will need to modernise and diversify its economy away from a reliance on the export of a few commodities. The rule of law, upholding rights and fighting corruption are important conditions to encourage investment and entrepreneurship. This provides the EU with some leverage and an opportunity to promote reform while building on economic interdependence.

A new opportunity to foster democratisation

The EU should use its leverage in two ways. First, including commitments to democratic reform in the negotiations over an enhanced PCA; and second, expanding cooperation on democratic reform as part of the new agreement, sustaining change over the long-term.

So far it has been foremost the European Parliament (EP) that has actively supported a values-oriented agenda in the negotiations. In October 2012, the EP adopted recommendations for the EEAS, the European Commission and the Council in which it sets standards for the negotiations, conclusion and implementation of the agreement.(6) The EP report stresses ‘that progress in the negotiation of the new PCA must be linked to the progress of political reform’ in Kazakhstan and insists on the possibility of suspension of the agreement in case of gross human rights breaches.

The EP’s proposals are rooted in the EU’s 2012 Strategic Framework and Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy,(7) which places values at the centre of the EU’s relations with third countries and connects democracy and human rights with other policy fields, such as trade and investment. Whether the EU lives up to such standards in its relations with Kazakhstan will largely depend on the formulation of the democracy and human rights clause in the new PCA and the inclusion of an actual suspension clause. Rhetorical reference to values in the current agreement has left many human rights violations overlooked and the country’s backsliding on democracy rather unattended. The closing of media outlets, an unfair electoral environment and elections marred with violations of basic international standards, slow and poor implementation of judicial reform and a lack of separation of powers have marked Kazakhstan’s backsliding on democratic reform. In order to make the best use of the EU Strategic Framework for Human Rights and democracy, the new PCA should specify what constitutes a severe human rights breach thus providing a viable ground for the potential suspension of the PCA, and include clearer democratic reform indicators. Introducing more precise language is challenging but not impossible, as long as the political will matches trade and investment interests.

While the European Parliament is not directly involved in the negotiations, it will vote on the agreement when talks are concluded, as well as monitor negotiations and the agreement’s implementation, as guaranteed by the Lisbon Treaty. To ensure that its recommendations are implemented, the Parliament has requested the establishment of a comprehensive monitoring mechanism that would include regular reports to the EP during the course of the negotiations and after the PCA is signed. But at the moment, no details have emerged about the format of these reports or the EP’s options for acting on them. The functions, mandate and structure of the comprehensive monitoring mechanism should be made transparent from the outset, including a clear modus operandi between the EP’s Foreign Affairs Committee and the EEAS. As the most outspoken actor in EU democracy and human rights promotion, the EP should be able to react effectively to developments in the negotiation process and remain proactive thereafter through a monitoring mechanism that serves as a tool of concrete influence.

Conclusion

It is unclear when negotiations on the new PCA will be concluded and what the outcome will be. It is not even certain that a new agreement will enter into force after talks are concluded because if the final text fails to include the EP’s recommendations, the latter has the right to postpone or reject the agreement.

The most positive, although least realistic, outcome would see the new agreement include democratisation, good governance, rule of law and respect for human rights as cornerstones. The then truly enhanced PCA would include trade, investment and democratic reform on an equal footing. Clearly articulated human rights clauses and benchmarks would serve to verify progress on political reform and human rights in accordance with a new and specific Human Rights Action Plan to be adopted by Kazakhstan. The European Parliament would help monitor progress and act within its mandate to ensure its recommendations are implemented. Another scenario would be the conclusion of a new PCA that lacks an advanced democracy and human rights agenda. In this case, the new PCA would not differ much from the vague formulations of the current agreement and would thus be less ‘enhanced’. A final scenario would involve prolonging the negotiations indefinitely, with the two parties unable to agree on the content and wording of the new PCA. This might be the most likely outcome, given the current stop-and-go pace of talks and Kazakhstan’s declining enthusiasm in view of the complex EU trade-related requirements and demands for political reform.

While difficult, the negotiations on an enhanced PCA with Kazakhstan present an opportunity for the EU to start putting its rhetoric about democracy and human rights into practice. As a normative actor, the EU should not shy away from taking up democracy and human rights matters in these negotiations and including them as a comprehensive part of this basic and probably long-lasting agreement. Ever-growing trade flows between Europe and Kazakhstan give the EU some leverage in bringing ‘values’ to the table, which could lead to better mechanisms to promote democratic reform and monitor Kazakhstan’s performance on democracy and human rights. Kazakhstan has made economic advances, but it will need to meet its democratic reform pledges if it wants to be seen as a modern country where investment is profitable and safe. Both the EU and Kazakhstan would draw considerable benefits from a new and truly Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement.

- The EU-Kazakhstan legal framework also includes a Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the field of Energy (2006), available at: http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/kazakhstan/documents/eu_kazakhstan/memorandum_field_energy_en.pdf and a Memorandum of Understanding in the Field of Transport Networks development (2009), available at: http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/kazakhstan/documents/eu_kazakhstan/memorandum_field_energy_en.pdf

- MFN treatment also provides favourable conditions for transit, payment methods and rules related to the sale, purchase and distribution of goods on domestic markets.

- Council of the European Union, ‘11th Cooperation Council, EU-Kazakhstan, 17 November 2009, Joint Statement’, available at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/er/111290.pdf

- Source: EU Crude Oil Imports http://ec.europa.eu/energy/observatory/oil/import_export_en.htm

- Promises and Hurdles in EU-Kazakhstan Energy Cooperation, Nargis Kassenova, EUCAM Commentary No. 20, November 2011 https://eucentralasia.eu/uploads/tx_icticontent/Commentary_02.pdf

- European Parliament Committee on Foreign Affairs, ‘Report containing the European Parliament’s recommendations to the Council, the Commission and the European External Action Service on the negotiations for an EU-Kazakhstan enhanced partnership and cooperation agreement’, 26 October 2012, available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=REPORT&reference=A7-2012-0355&language=EN

- Council of the European Union, ‘EU Strategic Framework and Action Plan in Human Rights and Democracy’, 25 June 2012, available at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/EN/foraff/131181.pdf